采采卷耳,不盈頃筐。嗟我懷人,寘彼周行。

陟彼崔嵬,我馬虺隤。我姑酌彼金罍,維以不永懷。

陟彼高岡,我馬玄黃。我姑酌彼兕觥,維以不永傷。

陟彼砠矣,我馬瘏矣,我僕痡矣。云何吁矣。

Translation by Arthur Waley, 1937 (from the 1996 Grove Press edition, edited by Joseph Roe Allen):

Thick grows the cocklebur;

But even a shallow basket I did not fill.

Sighing for the man I love

I laid it there on the road.“I am climbing that rocky hill,

My horses stagger,

And I stop for a little to drink from that bronze ewer

To still my heart’s yearning.I am climbing that high ridge,

My horses are sick and spent,

And I stop for a little while to drink from that horn cup

To still my heart’s pain.I am climbing that shale;

My horses founder,

My groom is stricken.

Oh, woe, oh, misery!”In the first verse it is the lady left at home who speaks; in the remaining verses it is the man away on a perilous journey.

Karlgren, 1950:

I gather the küan-er plant, but it does not fill my slanting basket (a); I am sighing for my beloved one; I place it here on the road of Chou.

I ascend that craggy height (b), my horses are all exhausted; meanwhile I pour out a cup from that bronze lei-vase, in order not to yearn all the time.

I ascend that high ridge, my horses become black and yellow (c); meanwhile I pour out a cup from that kuang-vase of rhinoceros (horn), in order not to be pained all the time.

I ascend that earth-covered cliff; my horses are sick; my driver is ill (d); oh, how grieved I am!

(a) I am working listlessly, with poor result. (b) To look for him. (c) Black-streaked with sweat and yellow with dust; the par. with st. 2 shows that hüan-huang ‘black and yellow’ does not mean the horse’s natural colour, but is a result of their labour. (d) The speaker is so restless that both team and coachman are driven to excessive exertions.

stanza 1 #

采采卷耳,不盈頃筐。嗟我懷人,寘彼周行

- Waley:

Thick grows the cocklebur; but even a shallow basket I did not fill. Sighing for the man I love, I laid it there on the road.

- Karlgren:

I gather the küan-er plant, but it does not fill my slanting basket; I am sighing for my beloved one; I place it here on the road of Chou.

1.1 Off the bat the translations differ in the first line, with Waley giving “thick grows [the plant]”, and Karlgren “I gather [the plant]”. This is due to different interpretations of the word 采采 *tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ. Karlgren follows the Máo gloss: 采采,事采之也 “*tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ means ‘to apply oneself to gathering it’”. According to M. the word 采采 *tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ is a reduplicative form of the verb *tsʰˤəʔ, “pick, gather”; also in Shī 8 there is 采采芣苢,薄言采之 (W.: “thick grows the plantain; Here we go plucking it”; K.: “we gather the plantain, we gather it”), with M. gloss 采采,非一辭也 “*tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ is a word that means ‘not singly’ (?)”—this is generally taken to mean that *tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ is *tsʰˤəʔ more than once; i.e. the redup. serves some iterative function. This has been the traditional explanation since the Hàn dynasty.

This interpretation has nevertheless been met with objection since 18 c. One complication is given by the varied glosses of this word—or at least this orthographic form—in the Máo recension of Shījīng. In Shī 129 there is 蒹葭蒼蒼 (W.: “thick grow the rush leaves”; K.: “the reeds and rushes are very green”) in the first stanza, 蒹葭萋萋 (W.: “close grow the rush leaves”; K.: “the reeds and rushes are luxuriant”) in 2nd st., and 蒹葭采采 (W: “very fresh are the rush leaves”; K.: “the reeds and rushes are full of colour”) in 3rd st. with M. glosses 蒼蒼,盛也 "*tsʰˤaŋ-tsʰˤaŋ means “luxuriant[ly growing]”, 萋萋,猶蒼蒼也 “*tsʰˤəj-tsʰˤəj is like *tsʰˤaŋ-tsʰˤaŋ”, and 采采,猶萋萋也 “*tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ is like *tsʰˤəj-tsʰˤəj”. Here, then, 采采 *tsʰˤəʔ-tsʰˤəʔ is not related to *tsʰˤəʔ “pick, gather” at all, but on its own a reduplicative binom [1] with the meaning “luxuriant”.

In Shī 150 yet one more instance of this word is found: 蜉蝣之翼,采采衣服 (W.: “wing-sheaths of the mayfly—clothes so bright and gay”; K.: “the wings of the ephemera—how colourful are the clothes!”), which M. glosses as “numerous, many” (采采,眾多也), though we have a third-hand record that the Hán 韓 school of the Shī glossed this as 盛也 “luxuriant[ly coloured]” (see Dīng 1940)—that is, the same as Máo’s gloss in Shī 129.

Suspicion has been repeatedly raised since 18 c. that the 采采 in Shī 3 and 8 are the same as that in 129 and 150, i.e. a binom meaning “luxuriant” (in 150 at least conceivably > “numerous”, but not necessarily). What makes the above more than suspicion, and what I think is the coup de grâce to the Máo-traditional reading, is the observation that the construction intended by Máo has no grammatical parallel in Shījīng: in Shījīng elsewhere, whenever such a reduplicative binom immediately precedes a nominal item, the former is always a modifier of the latter. An elucidation of this exegetic minutia is made in Dīng Shēngshù 丁聲樹 (1940, in Literary Chinese), Shī Juǎn-Ěr, Fǒuyǐ “cǎicǎi” shuō 詩 卷耳、芣苢「采采」說 (this essay can be found in the collection of Dīng’s Complete Works). On this point W.'s translation is perhaps more precise in meaning; K. has the point of sticking to the traditional reading.

1.2 頃筐, usually taken straightforwardly as 頃 [*kʷʰeŋ, “slanted, tilted”] + 筐 [*kʷʰaŋ, “basket”]; should be the name of a particular type of basket. M. gloss: 頃筐,畚屬,易盈之器也 “*kʷʰeŋ-kʷʰaŋ is the same kind as *pˤənʔ [also a kind of basket]; it is a vessel that is easily filled up”, hence must have been W.'s “shallow basket”.

stanzas 2, 3 #

陟彼崔嵬,我馬虺隤。我姑酌彼金罍,維以不永懷。

陟彼高岡,我馬玄黃。我姑酌彼兕觥,維以不永傷

- Waley:

I am climbing that rocky hill, my horses stagger, and I stop for a little to drink from that bronze ewer, to still my heart’s yearning. / I am climbing that high ridge, my horses are sick and spent, and I stop for a little while to drink from that horn cup, to still my heart’s pain.

- Karlgren:

I ascend that craggy height, my horses are all exhausted; meanwhile I pour out a cup from that bronze lei-vase, in order not to yearn all the time. / I ascend that high ridge, my horses become black and yellow; meanwhile I pour out a cup from that kuang-vase of rhinoceros (horn), in order not to be pained all the time.

2.1 In the version found on the Ānhuī University Bamboo slips 安大簡 (from the Chǔ 楚 state in the Warring States period) these two stanzas are in the opposite order to that of the Máo text. This of course does not affect the whole picture too much. The same excavated version has 維以永懷, 維以永傷 etc. instead of 維以不永懷, etc., which I can’t really make sense of—probably a scribal mistake?

2.2 崔嵬 is the familiar reduplicative binom *dzˤuj-ŋˤuj, usually glossed as “steep; high”. In this Shī 崔嵬 is used nominally (W. “rocky hill”, K. “craggy height”). The M. gloss says 崔嵬,土山之戴石者 “*dzˤuj-ŋˤuj is the kind of earthen hills with rocks on top”. A totally reduplicative form of the first element *dzˤuj-dzˤuj (崔崔) “steep, high” is found in Shī 101; the first element *dzˤuj is phonologically close to the synonymous items *dzut (崒, Shī 193) and *dzruŋ (崇, Shī 291)—all “steep, high”; the etymological relationship, if there is any at all, is unclear. Further note other semantically and phonologically related items, most of which first attested in Hàn (first attestations earlier than Hàn are noted), e.g. *dzˤaj-ŋˤaj (嵯峨), *dzˤat-ŋˤat? (嶻嶭), *ŋˤram-dzrˤam (巉巖; in Sòng Yù 宋玉 ca. 319–298 BCE, Gāotáng Fù 高唐賦), *dzew-ŋˤew (嶕嶢), *loŋʔ-tsˤoŋʔ (嵱嵷; redup. < *tsˤoŋʔ?); particularly concerning the second element of this binom there is further *ŋuj-ŋuj (巍巍; in Lúnyǔ), *ʔˤruj-ŋˤuj (崴嵬), *kʰrujʔ (巋; in Zhuāngzǐ). I have literally no idea what’s going on here, as is usually the case with these redup. binoms. But since both *TSUJ(-TSUJ) and *ŊUJ(-ŊUJ) have separate attestations in pre-Qín use, it’s conceivable that this is not an inseparable binom but two synonyms used in tandem that happen to rhyme.

(sidenote) I now do not believe what I argued in 2.3 is true. My reasoning in 2.4 therefore now needs rewording, which I will get to once I have the time. (

2024-4-6update)

2.3 Probably similar is the (pseudo-?) binom in parallel position in the next line, 虺隤 *hˤuj-lˤuj [2] (W. “stagger”; K. “all exhausted”), which M. glosses as 病也 “ill, sick”. 虺 *hˤuj is perhaps related to 壞, 瘣 *gˤrujs “ill, sick” (Shī 197) (< “destroyed”?) [3], and 隤 *lˤuj can stand as a morpheme on its own that means “to collapse”.

2.4 A tangent on the reconstruction of the item 隤 lˤuj and the 貴 series in general. One could divide this series into three parts: (1) items with posterior MC initials, e.g 貴 kjw+jH “precious”, 饋 gwijH “to provide with food”, 匱 gwijH “box”; [4] (2) items with the y- initial—the only common and reliably pre-Qín ones are 遺 ywij “to leave behind” and 遺 ywijH “to gift” (also note 壝 ywijX “low walls that enclose e.g. a sacrificial altar” [Zhōulǐ, Yìzhōushū] and 肥𧔥 bj+j-ywij some sort of mythical snake monster [Shānhǎijīng]); (3) items with MC coronal plosives—the only reliably pre-Qín one is 隤, 僓, 穨, 頹, etc., dwoj “to collapse”. Both Baxter & Sagart and Schuessler (the latter I’m not entirely sure about) seem to try to put (1) and (2) in the same series and deny (3) to have had pre-Qín XS contact with either (1) or (2) (both follow Karlgren in this division):

| item | inherited ortho. | B&S (2014) | Sch. (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|

| [kjw+jH “precious”] | (貴) | *kuj-s | *kwəs |

| [gwijH “to provide with food”] | (饋) | *[g]ruj-s | *gus |

| [gwijH “box”] | (匱) | *[g]ruj-s | *gus |

| [ywij “to leave behind”] | (遺) | *[ɢ](r)uj | *wi |

| [ywijH “to gift”] | (遺) | *[ɢ](r)uj-s | *wih |

| [dwoj “to collapse”] | (隤) | *N-rˤuj | *dûi |

B&S’s reconstruction for 隤 obviously tries to link it to 儽 *[r]ˤuj-s “exhausted” (see B&S 2014: 116).

In the AHU bamboo slip version the Máo-text 隤 in this line is written as what the scribers of the Warring-States Chǔ slips had usually used to write 遺 [ywij “to leave behind”]; [ywijH “to gift”]—basically rendering the division above invalid. In fact, it has been noted (e.g. in Zhào Tóng 趙彤, 2008, in Mandarin) that the Warring-States Chǔ scribers used one phonetic element for (1), and another, completely different phonetic element for (2) and (3) (all images in the table below except the last one are taken from www.kaom.net):

| item | inherited ortho. | Chǔ slips ortho. |

|---|---|---|

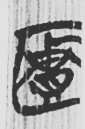

| [kjw+jH “precious”] | (貴) |  郭店.老子甲.12 (> v. “treasure”) |

| [gwijH “to provide with food”] | (饋) |  包山.卜筮祭禱.200 |

| [gwijH “box”] | (匱) |  清華.金縢.10 |

| [ywij “to leave behind”] | (遺) |  清華.良臣.8 (> “left-behind”) |

| [ywijH “to gift”] | (遺) |  上博.鶹鷅.1 |

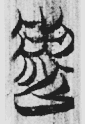

| [dwoj “to collapse”] | (隤) |  安大.周南.7 (in [xwoj-dwoj “ill, sick”]) |

This seems to me strong evidence that (2) and (3) were in one series distinct from (1) (the merger of the two to one single series is probably due to graphic confusion in the Qín lineage of the script):

| item | inherited ortho. | revised reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| [kjw+jH “precious”] | (貴) | *kujs/*kuts |

| [gwijH “to provide with food”] | (饋) | *grujs/*gruts |

| [gwijH “box”] | (匱) | *grujs/*gruts |

| [ywij “to leave behind”] | (遺) | *luj |

| [ywijH “to gift”] | (遺) | *lujs |

| [dwoj “to collapse”] | (隤) | *lˤuj |

2.5 The word 玄黃 *gʷˤin-gʷˤaŋ is usually taken to be a compound of 玄 *gʷˤin “dark-coloured” and 黃 *gʷˤaŋ “yellow”. Another attestation in Shījīng of this word is in Shī 154, in the largo form 載玄載黃, used to describe clothes, where the Máo commentary notes that 玄 is the colour for ritual clothing.

(sidenote) Nevertheless 玄黃 could be simplex, i.e. not actually a compound of 玄 and 黃; Zhū Guǎngqí 朱廣祁 (1985: 106) draws attention to orthographically varying but identifiable instances of this item, e.g. 轉轂連騎,炫熿于道 (Strategies of Qín 秦策 in the Strategies of the Warring States 戰國策), 青蔥苓蘢,萑蔰炫煌 (Teachings on the beginning of reality 俶真訓 in Huáinánzǐ 淮南子), 光色炫晃,芬馥肸蠁 (Zuǒ Sī 左思, Rhapsody of the Wú capital 吳都賦). Zhū notes that these all point to something like “vividly and dazzlingly coloured”. identification of 我馬玄黃 with this item is still semantically problematic notwithstanding. (

2024-4-4update)

Indeed in other early attestations 玄黃 typically refers to colours, especially associated with those of the sky and the earth (Yìjīng: 天玄而地黃 “Heaven’s (colour) is azure and earth’s is yellow”, trans. James Legge). The instance of 玄黃 in this Shī, which is used to describe sick and exhausted horses, and—since it appears in parallel position with 虺隤 *hˤuj-lˤuj “sick, ill” in st. 2 and 瘏 *dˤa “sick, ill” (also cf. Shī 155) in st. 4—itself must mean something like “sick, ill”, has no obvious parallel use cases elsewhere [5] and is very confusing. M. gloss: 玄馬病則黃 “when dark-coloured horses fall ill, they turn yellow.” Zhū Xī 朱熹 elaborates: 玄黃,玄馬而黃,病極而變色也 “*gʷˤin-gʷˤaŋ means that the horses, orinally dark, turn yellow. This change of colour is a result of extreme illness.” I’m really not knowledgeable in equine illnesses enough to evaluate the plausibility of this, [6] but K. must have been incredulous, since his explanation is not pathological: “black-streaked with sweat and yellow with dust; the par. with st. 2 shows that hüan-huang ‘black and yellow’ does not mean the horse’s natural colour, but is a result of their labour.”

Alternative explanations have been offered. Wén Yīduō 聞一多 (1948, vol.2: 113–114, in Literary Chinese) proposed that 玄黃 refers not to the colours of the horses, but to the colours that the horses see: in exhaustion the horses’ vision blurs, no longer seeing things but only colours. He also tries to connect 玄黃 *gʷˤin-gʷˤaŋ to 眩眃 *gʷˤinʔ-gˤunʔ? > hwenX-hwonX “(of eyesight) blurred”. Gāo Hēng 高亨 (1957: 12, in Literary Chinese) tentatively proposed that 玄黃 here could mean “sweating profusely”, connecting it to 泫 *gʷˤin “(usually of tears) to flow down” and 潢 *gʷˤaŋ “(of a body of water) great and deep”. I don’t think a convincing case is made with either of those explanations. Other than the fact that something was wrong with the horses, I’m still not sure what 玄黃 means here.

stanza 4 #

陟彼砠矣,我馬瘏矣,我僕痡矣。云何吁矣

- Waley:

I am climbing that shale; my horses founder, my groom is stricken. Oh, woe, oh, misery!

- Karlgren:

I ascend that earth-covered cliff; my horses are sick; my driver is ill; oh, how grieved I am!

3.1 吁 *m̥(r)a > xju, M. gloss 吁,憂也 “*m̥(r)a means ‘pained, anxious’” (also see Shī 199 云何其盱 and 225 云何盱矣; this 盱 very likely writes the same word, though M. gloss at 199 for 盱 is different: 病也 “sick, ill”). The orthographic form 吁 in the Máo text points XS wise to *hʷ(r)a > xju (B&S: *qʷʰ(r)a “pained”). This item has, based on the Máo orthography, been equated with 于, 吁 *hʷ(r)a an exclamation (> “to sigh, to lament”) since Zhū Xī. But the version on AHU bamboo slips writes this word with 無—this points to an OC form with original *m̥-, which must have merged with original *hʷ- by the time of Máo; the Máo orthography must have reflected the post-merger phonology, and identification with the exclam. is probably not valid then. This has been noted by Zhāng Fùhǎi 張富海 (2024 [2022], in Mandarin).

footnotes

I use the term “binom” to mean “simplex disyllabic morpheme”. ↩︎

My system of OC initials is basically the same as that of Schuessler’s, with pharyngealization following Baxter and Sagart. *h- here is essentially equivalent to B&S’s *qʰ-. ↩︎

B&S reconstructs *[r̥]ˤu[j] for this item 虺, considering it to be cognate to 儽 *[r]ˤuj-s “exhausted” (2014: 116) ↩︎

A sidenote here: the item 靧 B&S cite on (2014: 101) (their reconstruction: *qʰˤuj-s > xwojH, “wash the face”) is troublesome since it has some early palaeographic evidence that seems to point to *m̥ˤ-, and the orthographic form inherited by received texts 靧 is then dubious (perhaps a late invention after the loss of voiceless resonants). It also happens that if we remove 靧 xwojH herefrom, there is no longer any item with x- in this series. ↩︎

Arguably Shī 234 st.1 何草不黃 and st.2 何草不玄 (W: “What plant is not faded?” “What plant is not wilting?” K.: “What plant is not yellow” “What plant is not dark”) could be read as both 玄 and 黃 meaning “ill, sick”; the first to make this point, I think, was Wáng Yǐnzhī 王引之 (1766–1834). In the opposite direction, one could also argue for something like “(of a plant) yellow and dark” > “(of a plant) faded and wilting” > “(in general) ill, sick, wasting away” to explain how 玄黃 gained the meaning, although I haven’t seen anyone make this particular case. ↩︎

One point should be raised that (I think the first to mention this was Chén Huàn 陳奐 1786–1863) the M. gloss 玄馬病則黃 might actually be a scribal error of 馬病則玄黃 “when horses fall ill, they become *gʷˤin-gʷˤaŋ”, thus parallel in terms of sentence structure to the M. gloss 馬勞則喘息 “when horses grow tired, they wheeze for breath” under Shī 162. ↩︎